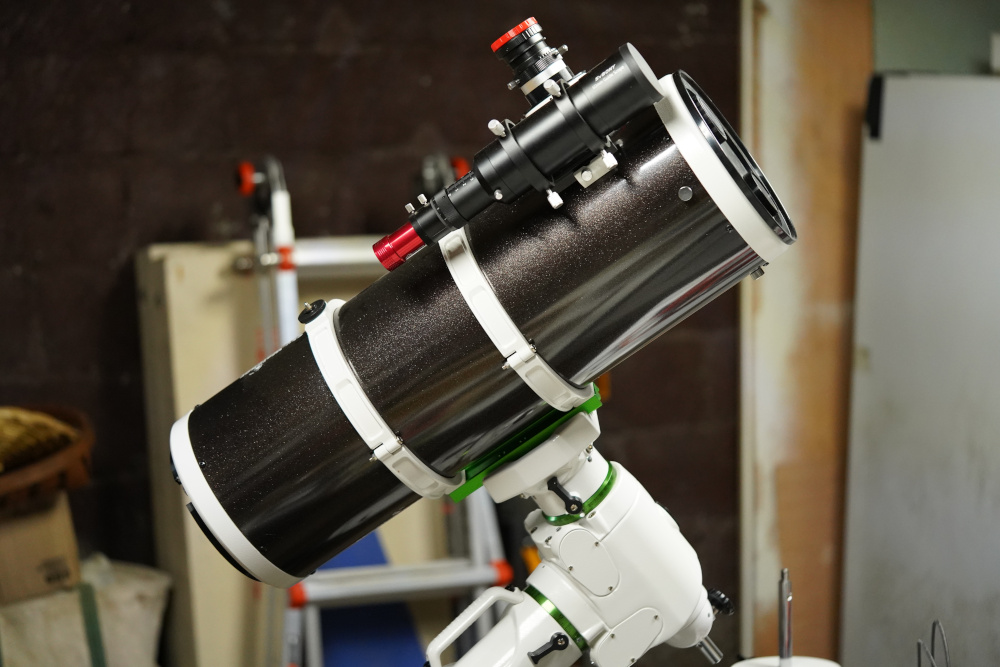

None of the images here were taken with this rig, but its where I started in 2010.

It’s been a while since my last post, largely due to time spent on beekeeping and astrophotograpy. So, to move the needle, I’ve pulled together some of the best images of deep-sky (meaning: far away) objects I’ve taken at night from the relatively light polluted (Bortle 7) Philadelphia suburbs. I’ve included with each image some notes about the acquisition, general information about the target (distance, type of object, etc), and a pretty thorough description of the visible objects (what am I seeing?). All of these images are from my yard, with streetlights and porch lights nearby, using a technique I described in a previous post to collect calibrated data for fighting light pollution.

I won’t go far into the details here, but basically I capture many long exposures of the same area of the sky with a relatively standard camera attached to a telescope on a very stable tripod that tracks the motion of the sky. That stage is nearly the same as having an 800mm focal length manual F/4 lens on a camera body, and in fact I took many of these images with a Sony mirrorless camera mounted to the telescope. Once I have that data I then apply a mathematical technique to combine these images together and extract very faint images of astronomical objects, which can be very far away.

The images below have some description of the object pictured and the details of the acquisition, but as they all share some common factors, let me first describe the rig that takes these pictures, and the processing that goes into making a human-viewable image.

The astrophotography rig

The images here were taken with this telescope, a SkyWatcher Quattro 200P (800mm fx F/4), on a Sky Watcher EQ6-R mount.

Auto-guiding for image stability

The mount is the crucial element of an imaging setup, and the EQ6-R is not one to disappoint. Without proper stability and fine motorized control of the pointing direction, correcting for the rotation of the Earth and taking long exposures will not be possible. In addition to simply correcting for the Earth’s rotation, this optical tube assembly (OTA) and mount combo are paired with another small telescope, a Svbony 60mm F/4 (240mm fx) doublet refractor, and a small ASI120MM monochrome camera, to enable real-time feedback control of the alignment. This guide scope and camera watches the sky constantly, and can be used to compute fine corrections to the pointing of the main telescope to ensure it does not drift from the desired target.

Computer control and feedback

To perform drift correction properly, a computer is needed to analyze the images from the guide camera and send correction commands to the mount. A computer is also very useful in that it can identify where the telescope is pointing by analyzing star positions, a process known as platesolving, as well as point the OTA at targets by name or position in a sky simulation, a superior goto experience to a remote or even phone app.

I’ve variously used a Surface Pro 3 (Windows - ancient), my aging daily-driver gaming laptop (7th gen i7, lots of ram and disk), and have finally landed on a Bee Link S12 Pro with a N100 processor to serve as the brains. The common factor here (except the surface, which was substantially underpowered) is Linux, where the KStars/Ekos software using INDI provide everything I need to control the telescope hardware I have and much more. The earlier work, including some featured here, in the Windows ecosystem used where NINA, PHD2, Stellarium and the ASCOM ecosystem serve largely the same purpose.

Deep-sky imaging cameras

Dedicated cameras exist for deep-sky astrophotography, and will often include a cooling mechanism to chill the sensor (results in less noise in the image) and fewer optical filters (which can block light in nebula). The marginally-known truth is that the best of these cameras are very similar to modern Sony mirrorless cameras except for those two factors, and often use the exact same sensors. Still, the astrophotography software out in the wild tend to support the dedicated cameras better, and their niche features are very useful for deep sky photography.

For my work, I’ve used both a Sony α7C 24MP full frame mirrorless camera and a ZWO ASI2600MC-Pro (using Sony’s IMX571 24MP APS-C sensor) dedicated astro cameras with all the bells and whistles. I had good experiences with the α7C, but ultimately decided full frame was not to my advantage in reach, pixel density, or telescope image spot size (the corners were not illuminated). The APS-C dedicated astro cameras were therefore really attractive, and I was happy to keep using my α7C exclusively for photography. The cooling does help noticeably reduce noise in the resulting data, and being able to see the deep-red light from glowing hydrogen made me a happy customer. It also helps that the APS-C sensor has the same number of pixels in a smaller form factor, giving it better sampling of my telescope’s image and effectively “more zoom” compared to the α7C.

Optical filtering and correction

I do have the recommended coma corrector for this telescope, and at F/4 it is very necessary for any reasonably sized sensor. This gives me a place to screw on 2" filters, so I’ve played around with that a bit. Filtering is more used at the “next tier” of astrophotography, where one uses monochrome cameras and R, G, B, or narrowband filters to take separate monochrome images that are later combined into a color image. That produces better results, some say, compared to the one-shot-color (OSC) cameras that are much more common in the wild. Dedicated astro cameras come in both flavors.

I remain with OSC cameras for now, where it sometimes makes sense to use dual narrowband, or even bandpass, filters to capture extremely faint signals or block light pollution. I have a Svbony H-alpha and O-III 7nm dual narrowband filter to capture the most common light of emission nebula while blocking light pollution, and a less-narrow “ultra high contrast” (UHC) filter from Astromania that aspires to accomplish the same thing. The dual narrowband filter will get some more time eventually, or perhaps I’ll upgrade to a better dual narrowband filter for the 2600MC. It does not get super impressive results with an unmodified camera or dedicated astro camera. That said, two of the images below utilized the UHC filter, which does produce OK results with the Sony body.

Finally: image processing

Besides the technique for acquiring data, which I said I would not go into, it is customary to do some substantial image manipulation to achieve the final image. I tend to avoid manipulation that strikes me as “dishonest” (like AI image enhancement – nonetheless very common in the wild) and stick to “standard” techniques like blackpoint adjustment, color balance, and simple noise reduction techniques like median kernels or downsampling. The big exception to this (in the “standard” but not “dishonest” department) is a technique called “image stretching” wherein a nonlinear transformation is applied to the pixel intensities to exaggerate some changes in brightness and de-emphasize others. My processing technique involves one initial stretch to bring the variation of intensity in the object of interest into a visually pleasing range of output intensities, followed by the more standard techniques above. Sometimes additional small stretches will be applied to emphasize details that got missed in the initial stretch.

The bulk of this process I have codified in a mostly-automated set of algorithms implemented in Python: oscdeeppy primarily for my own use, but available for free to others. This process is heavily inspired by the suggested processing steps from the Siril team, and indeed mix of my images were processed with Siril and my own software. I should really do a separate blog post on the use of oscdeeppy, but the repository contains a good example notebook that walks through the process visually.

Now to the fun part, in roughly chronological/experience order.

M42 – The Orion nebula

M42 & NGC1977 from December 12, 2023 – $35 \times 2 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (1h10m total) with the α7C. Acquired with NINA and PHD2. Processed with Siril. Click for full resolution.

This is one of the earliest images I took, and also includes NGC 1977 the Running Man nebula off to the left. The Orion nebula is a star-forming region visible to the naked eye as the “sword stars” in the Orion constellation, below the belt. Despite being an early image, there’s a lot of clear detail and low noise because this nebula is very bright from all the reflected starlight and hot glowing gas. The nebula is around 1300 light years away, within our own galaxy. It’s about 24 light years across spanning about 1 degree, or about two full moons, in the sky.

What am I seeing?

The colors here are all due to hot glowing gas (hydrogen – red, oxygen – blue), with density and temperature distributions viewed from a distance giving texture. Reflected starlight accounts for the remaining light (blues/grays). The dots are foreground and background stars.

Everything pictured here is a star or an optical artifact resulting from starlight. Note the different sized bright cores (proportional to brightness, not actual size), flare around the brightest stars, and diffraction spikes. Incidentally, the width of the diffraction spikes shows the focus size of the star, before the pixels spill over to make the core.

Stars have additionally color to them from redish to blueish that is proportional to its temperature. This is ultimately due to the physics of black body radiation and lets us measure the temperature of distant stars. Many of the bright stars here are hot blueish stars. Later images will have more variety.

IC434 – Horsehead nebula

IC434 and friends from December 21, 2023 – $40 \times 3 \mathrm{min}$ (2hr) unfiltered exposures plus $6 \times 10 \mathrm{min}$ (1hr) UHC filtered exposures (3hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with NINA and PHD2. Processed with Processed with Siril. Click for full resolution.

I include this one primarily because it’s well known for being very obviously the shape of a horses head. I haven’t yet taken a high quality image (in terms of noise) of the Horsehead yet, but now that I have a cooled astro cam that can see the red better, I am in a much better position to. The Flame nebula NGC 2024 & a reflection nebula NGC 2023 are also present in this shot. In addition to being in the Orion constellation, it is also physically nearby the Orion nebula at 1300 light years away from Earth. The very bright star with huge diffraction spikes (purely optical effects) is the leftmost belt star in the Orion constellation.

What am I seeing?

NGC2023 cropped from the above for clarity. This reflection nebula is not an optical artifact, unlike most other light around bright stars. The illuminating star is dead center.

Some stars here have a much more prominent bright cloud around them, notably NGC2023 just below and to the left of the Horsehead and in the crop to the right. Here, this is starlight reflected off the nearby nebula, and texture (light and dark regions of lower and higher density) can be seen. Compare this to the “flare” around the brightest star, which is an optical artifact instead of a reflection nebula. There is another good reflection nebula all the way to the left at the same vertical offset as the one below the Horsehead, and another near the bottom directly below the Horsehead.

The bottom half of the image probably at first appears to simply have fewer stars. On close inspection you can see the background stars are simply being blocked by the dark nebula that makes the horse head, which is the same nebula being illuminated to form NGC2023 and forming the dark part of the flame.

C49 – The Rosette nebula

C49 from December 22, 2023 - $6 \times 10 \mathrm{min}$ UCH filtered exposures (1hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with NINA and PHD2. Processed with Siril. Click for full resolution.

Another star-forming region apparently near the Orion constellation in the sky, but 5000 light years from us (much further than Orion’s 1300 light years), is the Rosette Nebula. This is the shortest exposure in this post at 1hr total integration time, but with 10 minute exposures using the UHC filter, it still came out quite good, if a bit grainy. Most of the variance in these long exposures is due to light pollution, so the grain (related to the variance) is substantially suppressed by reducing the amount of background light initially detected.

The majority of the light from these redish nebula is not collected by a consumer-grade camera, even the very fancy ones, as it’s at a relatively long wavelength compared to typical red hues. Dedicated astro cameras don’t have this issue, so I’ll revisit this one too. Nonetheless, it’s neat seeing the “small details” and the sort of three dimensional nature they impart.

What am I seeing?

Because only apparent brightness and temperature are evident in images of stars, and stars come in a very wide range of inherent luminosity, it is very difficult to know if a star is in the foreground or the background. All visible stars visible in my images are within our own galaxy, however, as stars from other galaxies will only be resolved as a gradient proportional to star density. More on that next.

In addition to diffraction spikes and flare seen before on bright stars, the Astromania UHC filter introduces a distinct ‘halo’ optical effect.

More prominent in this UHC filtered image than in the UHC and unfiltered combination for the Horsehead nebula is a “halo” around the brighter stars. This is a unique optical artifact of budget filters (Astromania is not quite what I would describe as a premium brand) lacking proper anti-reflection coatings. Without these coatings, the sensor sees an out-of-focus reflection of stars off the back of the filter, which appear as a halo.

M51 – The Whirlpool galaxy

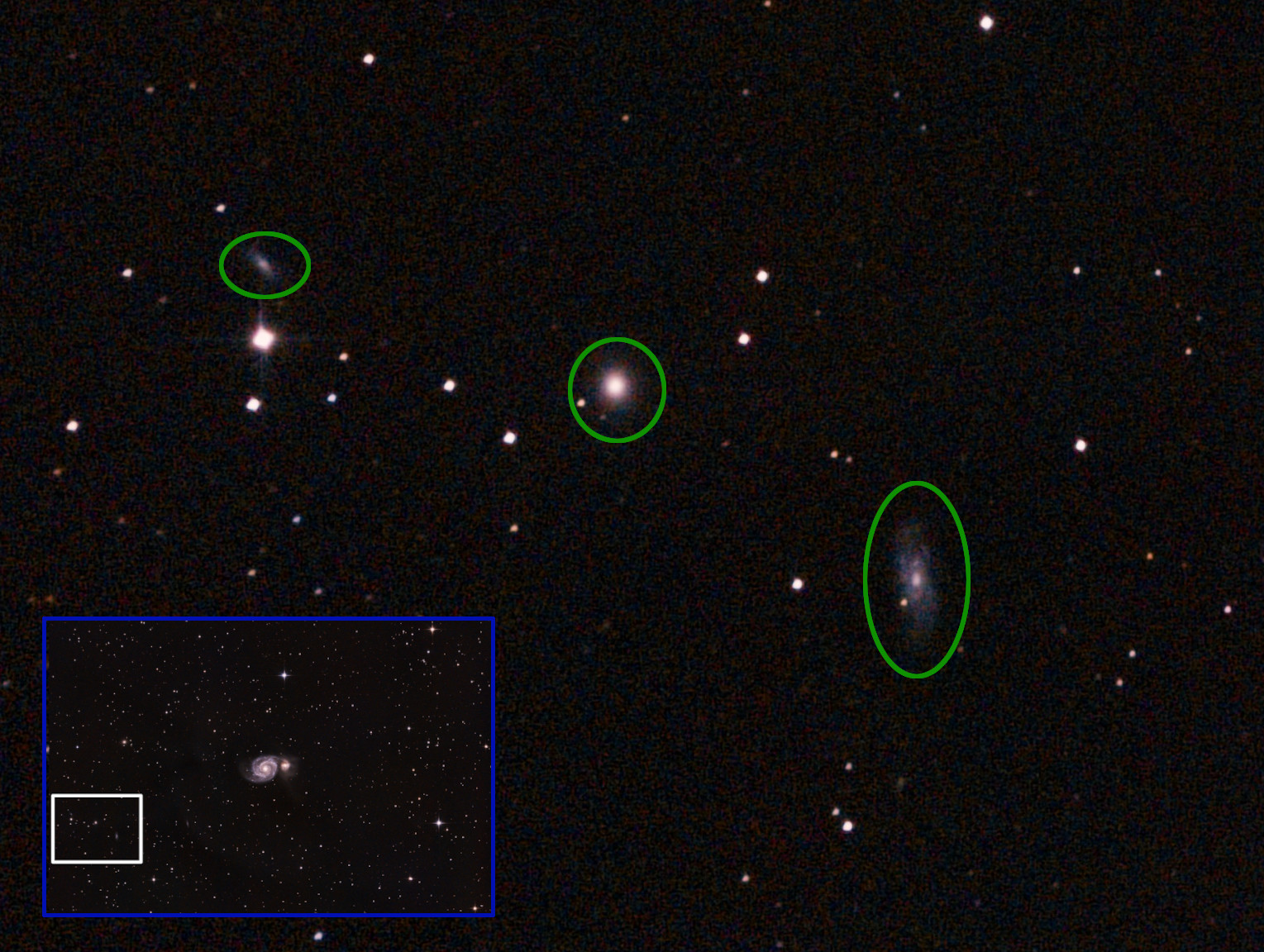

M51 from March 21, 2024 – $45 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. Click for full resolution.

If you don’t want to click the images for full resolution, here’s a 100% crop so you can see the limiting resolution of my rig with the α7C.

To some extent I can compensate for galaxies being dimmer targets in post processing by setting lower black levels, or applying harder stretches, but if you look closely you can see that begins to reveal imperfections in the background flatness. These imperfections are largely due to light (the street lights and porch lights referenced earlier) getting to the camera sensor by routes other than the primary and secondary mirror, which turn up as light or dark areas in an otherwise flat background.

I developed the oscdeeppy software this image was processed with some time after taking the data, but I found that the results from that approach preserved the most detail within the galactic arms. The results from Siril weren’t quantitatively worse, but the slight differences in the debayering and alignment methodology in oscdeeppy gave a slightly better looking result.

What am I seeing?

Compared to the nebula before within our own galaxy, the Whirlpool galaxy is nearly eighteen thousand times further away, making them immensely bigger and brighter structures to be visible at all to us. Indeed, all the light from the galaxies is just a haze of trillions of individual stars, including the dim wisps near the edges. The spiral structure is complicated, but more due to the evolution of stars tending to propagate as a wave combined with past collisions with other galaxies than with galactic rotation. All the fine detail is the star haze being occluded by big stretches of dust, which tends to clump together.

The brighter blue coloration represents star forming regions full of young stars which tend to be much hotter. This is partially due to hot stars burning through their hydrogen faster than cooler stars, making older stars biased towards cooler variants, and partially because stars expand and cool as they age. The more golden/redish regions will be the older cooler stars. Galactic cores tend to have enough stars to have blown away the dust long ago, leading to very little new star formation, and a generally older, redder population of stars. Towards the fringes, that dust collects and gets pressed back into new stars in a repeating cycle as stars die and return their material with catastrophic explosions or general off-gassing of hot material.

Crop of the background of the M51 image, showing some more distant galaxies: NGC5169 and NGC5173. The smallest was not labeled in the catalogs I had available, but is certainly known. The other dots in this image are stars in our galaxy.

The earlier nebula images were mostly stars for the simple reason that nebula tend to be within the plane of our own galaxy, and dust clouds block the view of more distant galaxies in that direction.

M65, M64, NGC3628 – The Leo Triplet

M65 M64 NGC3628 from March 29, 2024 – $60 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (4hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. Click for full resolution.

M65 has a bit more of a tilt, and its bright compact core is prominent. Big dust clouds block the star haze from this perspective. NGC3628 is nearly edge-on and its dust clouds block much of the light from the galaxies stars.

M66 has a similar look to the Whirlpool galaxy, and both are nearly face-on.

What am I seeing?

My favorite thing about this target is the variety in galaxies it demonstrates, and the different perspectives, all in one frame. There isn’t much to point out that hasn’t been discussed in other images, except that visible galactic clusters tend to be outside of the plane of our galaxy, leading to far fewer stars in the frame. Just one star bright enough for significant diffraction spikes results in a very “empty” feeling scene, despite containing three entire galaxies.

M27 – The Dumbbell nebula

M27 from August 30, 2024 – $54 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3h36m total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. Click for full resolution.

M27 crop for those not viewing the higher resolution versions.

At this point I was quite comfortable with my imaging setup, and the only limiting factor was really time, clear skies, and light pollution. As such, this image turned out pretty good, but the fainter features are not present to a significant degree. Similar to the other nebula, a revisit with the 2600MC would be good to get more detail and more of the red glow.

What am I seeing?

A formerly active star – now a white dwarf visible dead center – reached the end of fusable material in its core, and the resulting instability ultimately led to it shedding most of its mass as hot gas, creating what is known as a planetary nebula. The Dumbbell nebula is one of the brightest, and thus earliest discovered, examples of planetary nebula, and indeed most other examples are much further, dimmer, and smaller. This planetary nebula is approximately 2 light years across, and is still expanding.

NGC6992 - The Eastern Veil nebula

NGC6992 from Sept 4, 2024 – $20 \times 5 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (1h40m total) with the ASI2600MC-Pro @ -10C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. Click for full resolution.

I also shot this target in Dec 2023 for about 30m ($10\times3\mathrm{min}$) with my α7C, but the red light was very faint.

The detail, low noise, and general high quality of this image, even in spite of the relatively short sub-two-hour exposure, is a testament to the benefits of high pixel density and cooling. You could attempt to remove the infrared-cut filter from a standard camera to claim most of these wins, but the lack of cooling would still be a huge drawback. Probably worth the investment in a dedicated astro camera if you enjoy the hobby, all said and done.

What am I seeing?

The nebula here is a part of a larger structure known as the Cygnus Loop, which in whole is about three degrees, or six times the size of a full moon. Similar to the Dumbbell nebula and unlike the nebula shown before, this is not a star forming region but rather the remnant of a more catastrophic stellar death called a supernova. This is only the eastern part of of what ultimately is a shockwave, circular/spherical in shape, and 120 light years across, left over after a star exploded 2400 light years away from here some 20,000 years ago.

The light and heat of the explosion plus the remnant hydrogen and oxygen of the star and interstellar space nearby results in the same glowing reds and blues present in nebula associated with star forming regions. In time, this and other shockwaves will kick off the clumping of interstellar gas, resulting in new stars.

M33 – The Triangulum galaxy

M33 from September 7, 2024 – $40 \times 5 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3h20m total) with the ASI2600MC-Pro @ -10C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. Click for full resolution.

M33 crop of the core to see the limiting resolution for this acquisition.

I would have rotated the camera 90deg for this, but I still had not really figured out how to take proper flats, and was postponing modifications to the image train to get proper flats to process the Eastern Veil nebula data pictured above. I decided not to rotate and crop in post just to keep all these images at roughly the same scale, and I’ll admit it’s a curious framing.

All that said, this is probably the best image I’ve taken so far, and it’s been a journey getting here.

What am I seeing?

NGC604, the largest known hydrogen-alpha emission nebula in the ‘upper left’ of M33 as pictured above.

Triangulum is so close, that it, our galaxy, Andromeda, and a few much smaller galaxies are all part of a gravitational system called unceremoniously the Local Group of which Triangulum is the third largest. As such, unlike most other galaxies which are receding from us at high velocities, Triangulum is hurtling towards the Milky Way at 45 km/s, give or take. All of the Local Group will collide and combine some day, but we’ll be long gone by then.

And that’s where I’ll leave this.

Looking for more?

I keep a photo album of new images with many more targets that I update as I go along. The descriptions there are relatively brief, but I enjoyed making a periodic summary post, so perhaps more will show up here in the future!

>> Home