This is a post about an algorithm I developed over a decade ago to generate mouse movements that could be mistaken for actual human input. The algorithm, called WindMouse, has been used in many different places, as a quick google search will show, and often appears unattributed in stackoverflow questions, despite being licensed under the GPL. Since it’s seen rather wide use, and was presented by a much-younger me with little explanation, I figured it would perhaps be beneficial to provide some context and insight into the algorithm.

Context

I initially got into programming to automate games that required a large number of tedious or repetitive tasks. RuneScape is an excellent example, where one might have to perform some mundane task hundreds of thousands of times to reach a maximum level in some skill. These mundane tasks all boiled down to clicking some object in the game’s 3D-rendered environment. For example, mine a rock by clicking it, smelt ore by clicking a furnace, go to a bank to store metal by clicking map locations, repeat this loop by clicking between locations, thousands and thousands of times. In my opinion, the other content of the game can be interesting, but sinking the thousands of hours into the game to be able to enjoy the content is much less interesting. And that’s where the desire to automate the game comes in.

Automation

Game automation can be broken down into three main efforts:

- Identify the state of the game

- Design an algorithm to determine what to do next

- Perform the desired actions

For a computer game like RuneScape that takes place in a simulated 3D world, the identification of the game state can be the trickiest part. The algorithm that decides what to do next is typically as simple as following a list of pre-determined instructions for the mindless automation goal, but can be arbitrarily complicated for more complicated games or tasks.

Here, I’ll only discuss the last point, which is performing the desired action. For computer games, this boils down to clicking something on the screen or pressing a key. General purpose API exist to do both things, like the pyautogui package, so it is straightforward to write simple code to interact with most games. You could even go further and run the game in a purpose-built sandbox with methods for interrogating and interacting with the game state, or use something more generic like a virtual machine to abstract game input.

Cat-and-mouse

The problem, of course, is that game-makers typically don’t like people automating their games, either because they profit off of advertisements (which you don’t see when automating), or because they feel that automated accounts detract from the game in some way. If you’re caught automating, you’re typically excessively punished, up to and including permanent removal from the game. The trick, therefore, is to automate in a nominally undetectable way. The most significant factor here is playing the game as a human would, by performing actions in a manner consistent with a human player. A less significant (and possibly totally unimportant) factor is interacting with the game as a human would, which might include details like:

- How fast a person can react to and click an object

- How quickly and accurately the mouse can be moved

- The precise detail of how the mouse is moved

Many mouse motion APIs will instantly move your mouse from its current location to the desired location. More advanced APIs will perhaps include linear interpolation to generate intermediate points in a straight line. Either could be a huge red flag for game-makers on the watch for automated accounts, and would be easy to detect The goal of human mouse movement is to obfuscate the fact that an algorithm is playing the game by generating mouse paths that are nominally indistinguishable from a human moving the mouse. This (hopefully) helps to keep one in good standing with the powers-that-be by making the automation just that much more human.

Mouse movement

From the perspective of a program receiving mouse motion information, a moving mouse is represented as a series of location updates at relatively fixed intervals typically around 10 ms (100 Hz), though some systems may update as fast as ever 1ms (1000 Hz). Either is fast enough for normal mouse movement to appear smooth. Each location update will provide only the location of the cursor (in pixels) at the time of the update. Even though the information delivered by mouse updates is limited, for each step is it possible to compute:

- Time elapsed since last step

- Change in position from last step

- From distance and time, the velocity

All of these metrics could be easily collected and compared to distributions typical of a human being to identify automated accounts. Empirical testing suggests humans move the mouse somewhere between 5-10 px/ms, but the exact value here depends on screen resolution, the display DPI, the user’s mouse settings, and the exact task being performed. Suffice to say, the mouse speed should be an input to any mouse movement algorithm, and should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

A human moving a mouse rarely moves in a straight line, instead having significant variations in direction. An easy way to see this is to open some drawing program, choose a brush with 1px width, and draw some lines at moderate speed. Moving fast enough, you may even be able to see the discrete times at which the mouse location is updated.

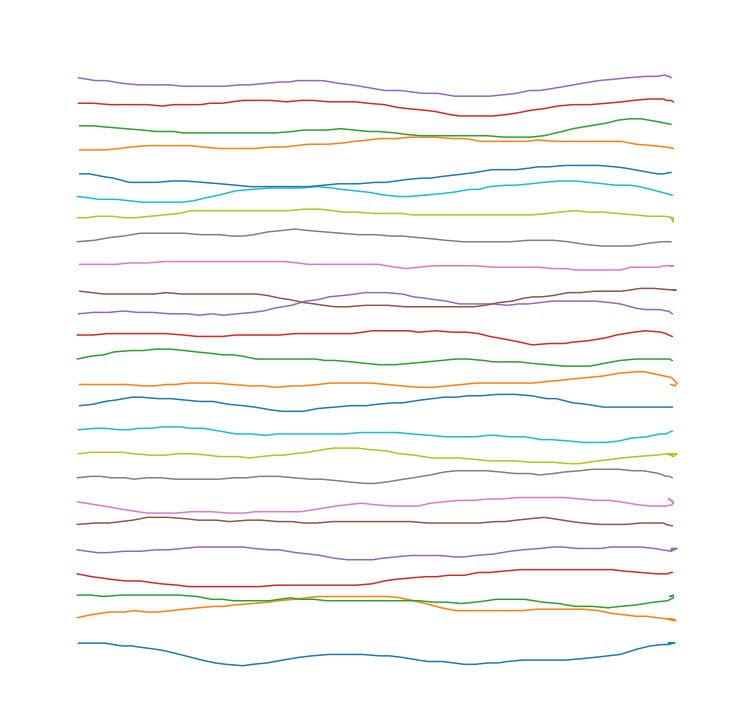

Some examples of a real human moving the mouse across the screen, captured in GIMP.

A simple linear interpolation that satisfied any human-mouse-speed assumptions would be easily identifiable as non-human when the angular distribution was observed, as it would have segments of discrete angles for each line. Replaying a finite set of real mouse movements would also be identifiable observing angular distributions. It is therefore critical to have some random algorithm that creates an acceptable angular distribution of steps, while still moving to a destination. The time distribution is relatively straightforward to satisfy, but the generation of paths with sufficiently human qualities is where WindMouse comes in.

WindMouse

The WindMouse algorithm is inspired by highschool physics that me-of-fifteen-years-ago was just getting interested in. The cursor is modeled as an object with some inertia (mass) that is acted on by two forces:

- Gravity, which is constant in magnitude (a configurable parameter) and always points towards the final destination.

- Wind, which exerts a random force in a random direction, and smoothly changes in both magnitude and direction over time

The total force on the object $\vec{F}$ is therefore a sum of the time-dependent wind $\vec{W}(t)$ and position-dependent gravity $\vec{G}(\vec{x}(t))$. $$ \vec{F}(t) = \vec{W}(t) + \vec{G}(\vec{x}(t)) $$ Since the force on an object is the second derivative of position by Newton’s second law, $$\vec{F} = m\vec{a} = m \ddot{\vec{x}}$$ this force could be integrated twice to get an expression for the position. $$ x(t) = \int_0^t \int_0^t F(\tau) d\tau^2 $$ In practice, since the wind force will not be easy to integrate analytically, and the gravitational force depends on position, numerical integration will be used. For numerical integration, it’s easier to beak a double integral into two single integrals, if possible. Here the velocity of the cursor would be the integral of the force. $$ \vec{v}(t) = \int_0^t \vec{F}(\tau) d\tau $$ The velocity can then be integrated once to find the position. $$ \vec{x}(t) = \int_0^t \vec{v}(\tau) d\tau $$ While the force is integrated to find the velocity, the velocity itself can be integrated to find the position.

A further approximation, to ensure that the output is always well behaved and within the realm of human behavior, clips the velocity to a random, smaller magnitude $M$ between $(\frac{M_0}{2},M_0)$ if it goes above a certain value.

$$ \vec{v}_i’ = M \frac{\vec{v}_i}{|\vec{v}_i|} \,\,\,\,\,\, \mathrm{if} \,\,\,\,\,\, |\vec{v}_i > M_0| $$

This acts somewhat like a terminal velocity, without explicitly including a drag force.

Integration

There are methods to integrate such problems correctly, which should be used in situations where one cares about accuracy. Considering that these are made up forces, which aren’t necessarily a correct model for anything, accuracy is much less of a concern. This was initially designed to run within the notoriously slow PascalScript interpreter, so instead of accuracy, execution speed is a much larger concern, and the integration algorithm had better spit out a new mouse position every 10ms at a minimum.

With that in mind, a very crude numerical integration technique is be used, with fixed time slices indexed by $i$ separated by $\Delta t$.

$$ \vec{v}_{i+1} = \vec{v}_i + \vec{F}_i \Delta t $$

$$ \vec{x}_{i+1} = \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_i \Delta t $$

With $\vec{v}_0 = (0,0)$ and $\vec{x}_0$ set to the start mouse position. It is then relatively straightforward to calculate $\vec{F}(i \Delta t)$ at the time of the $i$th slice, and iteratively both the velocity and the position. This process can terminate once the position is sufficiently close to the destination.

In most implementations, units of constant are adjusted such that $\Delta t = 1$, since this is physics, not math.

Gravity

The full expression for gravity is simple. With the destination point defined as $\vec{x}_f$ and $\vec{x}$ being the position the gravity is evaluated at, $$ \vec{G}(\vec{x}) = G_0 \frac{\vec{x}_f - \vec{x}}{|\vec{x}_f - \vec{x}|} $$ where the magnitude of the gravity is the constant $G_0$ and the vector component simply ensures the force is pointed at the destination. This term ensures the cursor will tend to approach the destination point.

Wind

The modeling of the wind is what gives WindMouse its characteristic behavior and name. The force on the cursor is modeled as a vector with $W_x$ and $W_y$ components. There is no explicit time dependent behavior of the wind. Instead, to achieve qualitatively human behavior, there are two update rules for each time slice, depending on how far the current location is from the destination.

-

Far from the destination, the previous step’s wind is reduced by a factor (historically $\sqrt{3}$) and a random value in the range $(-\frac{W_0}{\sqrt{5}},+\frac{W_0}{\sqrt{5}})$ is added to each component. This causes the wind to fluctuate smoothly from one step to the next, as if it is the velocity of something with some momentum that is perturbed by a truly random force, and the force experienced by the cursor is some form of drag.

-

Close to the destination, the previous step’s wind is simply reduced by a factor of $\sqrt{3}$. This lets the cursor more easily converge to the destination under the influence of gravity, and produces occasional overshoot-and-correct behavior when the final wind direction is somewhat perpendicular to the direction to the destination. The $M_0$ constant that clips the velocity is also reduced by a factor of $\sqrt{3}$ each step, to a minimum of $3$, to slow the mouse as it approaches.

These two behaviors result in a rapid-but-uncontrolled approach to a destination from a distance, with a more controlled-zeroing-in to the destination as it gets closer.

The Code

There are old and official (GPL licensed) versions of WindMouse in Java and Pascal but for this post I’ll present a 2021 version in Python (also GPLv3).

import numpy as np

sqrt3 = np.sqrt(3)

sqrt5 = np.sqrt(5)

def wind_mouse(start_x, start_y, dest_x, dest_y, G_0=9, W_0=3, M_0=15, D_0=12, move_mouse=lambda x,y: None):

'''

WindMouse algorithm. Calls the move_mouse kwarg with each new step.

Released under the terms of the GPLv3 license.

G_0 - magnitude of the gravitational fornce

W_0 - magnitude of the wind force fluctuations

M_0 - maximum step size (velocity clip threshold)

D_0 - distance where wind behavior changes from random to damped

'''

current_x,current_y = start_x,start_y

v_x = v_y = W_x = W_y = 0

while (dist:=np.hypot(dest_x-start_x,dest_y-start_y)) >= 1:

W_mag = min(W_0, dist)

if dist >= D_0:

W_x = W_x/sqrt3 + (2*np.random.random()-1)*W_mag/sqrt5

W_y = W_y/sqrt3 + (2*np.random.random()-1)*W_mag/sqrt5

else:

W_x /= sqrt3

W_y /= sqrt3

if M_0 < 3:

M_0 = np.random.random()*3 + 3

else:

M_0 /= sqrt5

v_x += W_x + G_0*(dest_x-start_x)/dist

v_y += W_y + G_0*(dest_y-start_y)/dist

v_mag = np.hypot(v_x, v_y)

if v_mag > M_0:

v_clip = M_0/2 + np.random.random()*M_0/2

v_x = (v_x/v_mag) * v_clip

v_y = (v_y/v_mag) * v_clip

start_x += v_x

start_y += v_y

move_x = int(np.round(start_x))

move_y = int(np.round(start_y))

if current_x != move_x or current_y != move_y:

#This should wait for the mouse polling interval

move_mouse(current_x:=move_x,current_y:=move_y)

return current_x,current_y

Examples

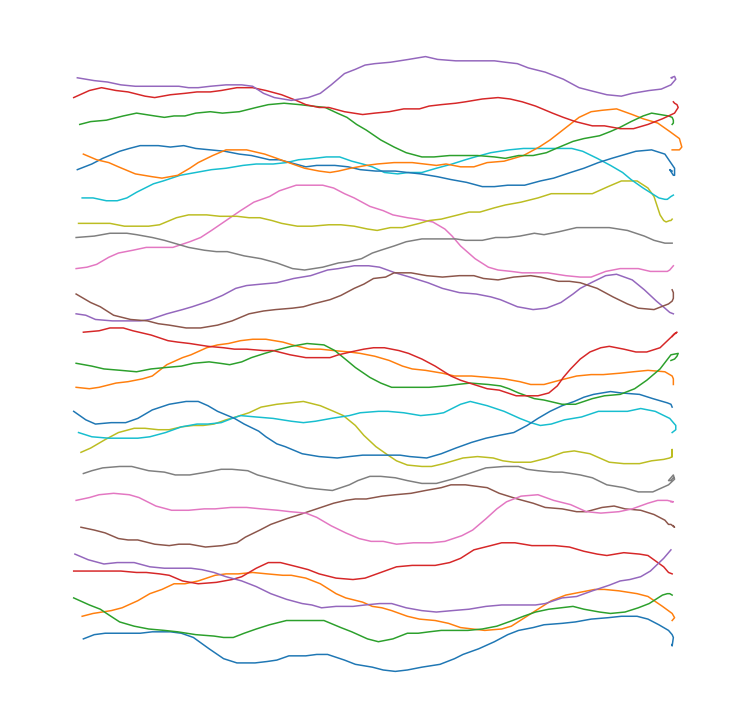

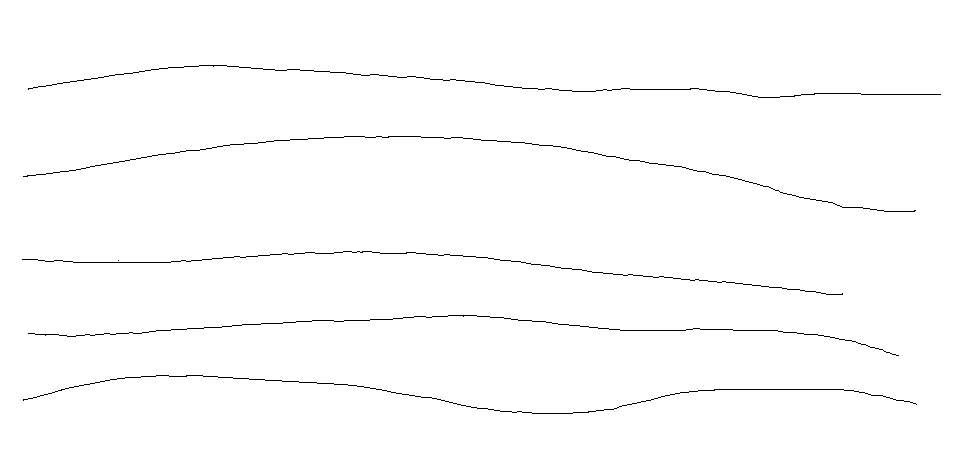

With the Python code above, it is straightforward to make some example movements and plot them.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=[13,13])

plt.axis('off')

for y in np.linspace(-200,200,25):

points = []

wind_mouse(0,y,500,y,move_mouse=lambda x,y: points.append([x,y]))

points = np.asarray(points)

plt.plot(*points.T)

plt.xlim(-50,550)

plt.ylim(-250,250)

Some examples of a WindMouse generating random paths across the screen. Generated with default parameters. Some examples of a WindMouse generating random paths across the screen. Generated with wind parameter boosted to be equal to the gravity parameter.