The dust matching game

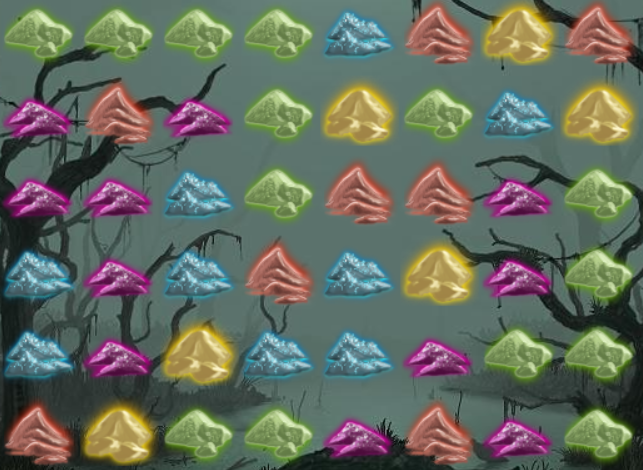

I was presented with a simple puzzle minigame from the MMORPG Nodiatis, which I had never heard of and know nothing about.

I have quite a history of automating computer games with tedious mechanics (looking at you, RuneScape), so I couldn’t resist taking a stab at this one.

The minigame consists of a 8x6 grid of five different colored piles of stuff (dust?) randomly selected for each position.

In a mechanic reminiscent of Bejewled or Candy Crush, one selects a particular pile, and any similarly colored connected tiles are removed from the grid.

Then any piles above a void fall down, and tiles are pulled towards the center to remove other voids.

Or so I’m told… at any rate, the goal here is to clear the board in as few moves as possible, where 10-12 moves is really good (gets you stuff), and >16 is not so good (gets you no stuff).

So the question becomes: given a board and the rules of this game, what is the optimal solution?

In a mechanic reminiscent of Bejewled or Candy Crush, one selects a particular pile, and any similarly colored connected tiles are removed from the grid.

Then any piles above a void fall down, and tiles are pulled towards the center to remove other voids.

Or so I’m told… at any rate, the goal here is to clear the board in as few moves as possible, where 10-12 moves is really good (gets you stuff), and >16 is not so good (gets you no stuff).

So the question becomes: given a board and the rules of this game, what is the optimal solution?

Solving the puzzle

First note that the number of possible options at any given board is equal to the number of clusters of unique elements on that board. That means there is somewhere around 25-30 options to start a randomly initialized board. The contracting mechanic can both create more clusters or fewer clusters depending on how the piles move around, but in general one can expect one to several fewer options on the next board. This continues until the board is past mostly empty (around 8-12 moves in) where options drop rapidly through the single digits for 2-4 more turns. That means there are (ballpark, from a medium difficulty board) about $$ 28\times25\times22\times21\times16\times13\times12\times8\times5\times3\times1 = 96864768000 $$ or a hundred billion possible ways to play a board with an 11 move solution. That’s a lot of possible boards to search to find a solution in the middle of the “really good” range, and it’s only worse considering typically there is no way to know an 11 move solution exists. In principle a board may not be solvable in fewer than 14+ moves, with a worst possible case somewhere in the high teens.

Assuming you can evaluate a board and decide on next moves in just a few hundred clock cycles (quite a feat!) on a modern computer, this means each board considered will take around $$ 100\times10^9 \mathrm{\ boards} \times 100 \mathrm{\ cycles/board} \times 10^{-9} \mathrm{\ seconds/cycle} \approx 3 \mathrm{\ hours} $$ to find a good solution and ensure there isn’t a better one with a brute force method. That’s no good! To be useful, solutions will need to be available in under a minute, since this is the time limit for the game. One also does not want to wait around for hours, even if the game didn’t care.

The ideal method to approach this problem ultimately will be a brute force depth first search of all possible moves to find the best one. Brute force is required because there’s no trivial way to know how a game will play out without, well, playing it. The complexity of the contraction mechanic is the primary reason for this. A depth first search is required because there is no feasible way to represent even a significant fraction of the ballpark 100 billion possible boards in a standard computer’s memory with tens of gigabytes of storage space. To do this, an abstract version of the game that can be played very fast by a solving algorithm will need to be constructed.

Abstracting the puzzle

To create something quickly, Python is always the language of choice, but to create something fast, one typically turns to compiled languages like C++.

This game has five colors that will be represented in printouts as green G, orange O, red R, yellow Y, and blue B and by the numbers 1-5 in the abstract game.

0 or will be the empty spaces on a board.

Some std::map objects can convert between these:

map<char,int> conv_to;

map<int,char> conv_from;

conv_to[' '] = 0;

conv_to['G'] = 1;

conv_to['O'] = 2;

conv_to['R'] = 3;

conv_to['Y'] = 4;

conv_to['B'] = 5;

conv_from[0] = ' ';

conv_from[1] = 'G';

conv_from[2] = 'O';

conv_from[3] = 'R';

conv_from[4] = 'Y';

conv_from[5] = 'B';

The 8x6 game board can be represented by a 2D array of integers of the correct size, which will be the grid type:

#define NSYM 5

#define W 8

#define H 6

typedef int grid[W][H];

grid board;

Simulating the game

Now it’s time to implement the game logic itself, which consists of the ability to clear groups and contract voids.

Clearing will be done with a flood fill algorithm, where a starting x, y position is given, along with the value being cleared.

void clear(int x, int y, int val) {

if (x<0 || x>=W || y<0 || y>=H) return;

if (board[x][y] == val) {

board[x][y] = 0;

clear(x-1,y,val);

clear(x+1,y,val);

clear(x,y-1,val);

clear(x,y+1,val);

}

}

The contraction is implemented by searching for 0 in the board and swapping them with the next value in the direction of contraction: down, left, or right.

void contract() {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) { // for each column

int y_to = 0;

int y_from;

while (y_to < H-1) { // down

while (y_to < H-1 && board[x][y_to]) y_to++;

if (y_to >= H-1) break;

y_from = y_to+1;

while (y_from < H && !board[x][y_from]) y_from++;

if (y_from >= H) break;

board[x][y_to] = board[x][y_from];

board[x][y_from] = 0;

y_to++;

}

}

for (int y = 0; y < H; y++) { // for each row

int x_to;

int x_from;

x_to = 4;

while (x_to < W-1) { // left

while (x_to < W-1 && board[x_to][y]) x_to++;

if (x_to >= W-1) break;

x_from = x_to+1;

while (x_from < W && !board[x_from][y]) x_from++;

if (x_from >= W) break;

board[x_to][y] = board[x_from][y];

board[x_from][y] = 0;

x_to++;

}

x_to = 3;

while (x_to > 0) { // right

while (x_to > 0 && board[x_to][y]) x_to--;

if (x_to <= 0) break;

x_from = x_to-1;

while (x_from > 0 && !board[x_from][y]) x_from--;

if (x_from < 0) break;

board[x_to][y] = board[x_from][y];

board[x_from][y] = 0;

x_to--;

}

}

}

These two components are combined into a single move operation, which contains everything that happens when clicking a position in the game.

void move(int x, int y) {

int val = board[x][y];

if (val != 0) { // only clear nonzero locations

clear(x,y,val);

contract();

}

}

Analyzing the game state

Now that there is a working simulation of the game, add utilities to aid the solving process.

Like the game simulation itself, these methods will be called many times, so be mindful about the complexity and algorithmic optimizations.

The simplest of these is a routine done to identify when the board is solved by checking the bottom row is all 0.

A board is is known to be unfinished if any nonzero element is encountered.

bool done() {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

if (board[x][0] != 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

As shown in the next section, a very useful thing to know about a board is the number of unique colors remaining. This is a deceptively simple thing to do, and this method will be called more than any other method, so any algorithmic optimizations here are critical for total runtime. For instance, once all colors are seen, return immediately, and do nothing for symbols that have already been seen.

int unique() {

bool seen[NSYM] = {false};

int count = 0;

for (int y = 0; y < H; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

if (board[x][y] && !seen[board[x][y]-1]) {

seen[board[x][y]-1] = true;

count++;

if (count == NSYM) return NSYM;

}

}

}

return count;

}

Finally, in any brute force search, the key to reducing total runtime is to not redundantly or unnecessarily search possible solutions.

Here, this means that instead of simulating clicking each location on the board (which would have $48! = 10^{61}$ total possibilities), one only needs to simulate clicking each cluster (only $\approx 10^{11}$ possibilities).

To do this, a routine to identify the clusters must be defined, where a cluster will be described as a cluster_result:

typedef struct {

int x,y; // one position in the cluster

int val; // the symbol value

int num; // the number of elements in the cluster

} cluster_result;

To find clusters, a flood fill that keeps track of which locations have already been clustered will be employed.

This is the most expensive single part of the board solver, but it only needs to be called for boards actively being explored by the solving algorithm.

This employs std::sort to order the clusters by biggest first.

int cluster_flood(int x, int y, int val, int cluster, grid &clusters) {

clusters[x][y] = cluster;

int accum = 1;

if (x > 0 && clusters[x-1][y] == 0 && val == board[x-1][y]) accum += cluster_flood(x-1,y,val,cluster,clusters);

if (y > 0 && clusters[x][y-1] == 0 && val == board[x][y-1]) accum += cluster_flood(x,y-1,val,cluster,clusters);

if (x < W-1 && clusters[x+1][y] == 0 && val == board[x+1][y]) accum += cluster_flood(x+1,y,val,cluster,clusters);

if (y < H-1 && clusters[x][y+1] == 0 && val == board[x][y+1]) accum += cluster_flood(x,y+1,val,cluster,clusters);

return accum;

}

vector<cluster_result> cluster() {

vector<cluster_result> cluster_results;

grid clusters = {0};

int next_cluster = 1;

for (int y = 0; y < H; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

if (clusters[x][y] == 0 && board[x][y] != 0) {

cluster_result c;

c.val = board[x][y];

c.x = x;

c.y = y;

c.num = cluster_flood(x,y,board[x][y],next_cluster,clusters);

next_cluster++;

cluster_results.push_back(c);

}

}

}

sort(cluster_results.begin(),cluster_results.end(),

[](cluster_result &a, cluster_result &b) {return a.num > b.num;});

return cluster_results;

}

Encapsulating the game

Package up the methods described in previous sections into a class so that the soon-to-be-described solving algorithms can use a nice object-oriented approach to finding solutions. This additionally includes ways to initialize random boards, display the board state, and save/load a particular state to/from strings.

class Board {

protected:

grid board;

void clear(int x, int y, int val);

void contract();

int cluster_flood(int x, int y, int val, int cluster, grid &clusters);

public:

// create a random board

Board() {

for (int y = 0; y < H; y++) {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

board[x][y] = rand() % NSYM + 1;

}

}

}

// initialize a board from a string representation

Board(const string &bstr) {

int i = 0;

for (int y = H-1; y >= 0; y--) {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

board[x][y] = conv_to[bstr[i++]];

}

i++;

}

}

// copy another board's state

Board(const Board ©) {

memcpy(board,copy.board,sizeof(board));

}

void move(int x, int y);

bool done();

vector<cluster_result> cluster();

int unique();

int get(int x, int y) {

return board[x][y];

}

// print a nicely formatted board to console

void print() {

printf(" | 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7\n--+----------------\n");

for (int y = H-1; y >= 0; y--) {

printf("%i | ",y);

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

printf("%c ",conv_from[board[x][y]]);

}

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

}

// print a serialized version of the board (for Board(string))

void output() {

for (int y = H-1; y >= 0; y--) {

for (int x = 0; x < W; x++) {

printf("%c",conv_from[board[x][y]]);

}

printf(y>0?",":"\n");

}

}

};

Now one can get pretty console printouts of the abstracted game. For instance, the image in the first section, abstracted:

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O Y O

4 | R O R G Y G B Y

3 | R R B G O O R G

2 | B R B O B Y R G

1 | B R Y B B R G G

0 | O Y G G R O R G

Or partway through the best solution to that board:

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | R O Y

3 | R R R O O B

2 | B R B B Y R

1 | B R B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

Solving strategy

The first thing to get out of the way here is that there are a lot of possibilities to consider, and there’s likely no way to quickly consider them all. The goal, therefore, should be to quickly identify an optimal solution rather than attempting to find the best solution. If a short enough optimal solution can be found quickly (a solution in fewer than 12 move), then it is computationally feasible to exclude the existence of any shorter solution. If only a longer solution can be found quickly, it is computationally intractable to exclude shorter solutions.

There are two robust shortcuts one can utilize to limit the number of possibilities to consider, and one is really an extension of the other. The first shortcut is that if a solution of length $N_{best}$ is found, then any search can be aborted once it requires $N \ge N_{best}$ steps. Here, a search is aborted when possible moves no longer need to be considered, and the search will resume at a higher level of the search tree. This prevents the depth first search from wasting time trying to exclude solutions longer than the current best.

The second (the extension) is that if a solution of length $N_{best}$ is found, than any search can be aborted once the number of unique colors on the board $M$ plus the current number of steps $N$ satisfies the relation $N+M \ge N_{best}$. This $M$ value places a robust bound on the minimum number of moves to clear a board without having to consider any particular moves. It is much faster to count unique colors on a board than to individually test all possible moves, so this saves a lot of time.

Many heuristics were considered to find an optimal order to search moves. The most straightforward is the heuristic to click the biggest clusters first. Here the search would click the biggest cluster on the board’s initial state, then click the biggest cluster created, etc. This chain terminates with a solution if the board is cleared, or aborts if the number of steps satisfies the criteria above. In the case of an abort, the algorithm next tries: biggest cluster, biggest cluster, …, next biggest cluster, and so on, in the depth-first fashion. Eventually it will try: next biggest cluster, biggest cluster, …, biggest cluster. I call this the “standard” method, and it is implemented as follows:

//returns the moves in backwards order ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

vector<cluster_result> dfs_cluster_solve(Board &b, int depth = 0, int max_depth = 48) {

vector<cluster_result> best_solution;

const vector<cluster_result> &clusters = b.cluster();

//sorted by cluster size (biggest first)

for (int i = 0; i < clusters.size(); i++) {

Board trial(b);

trial.move(clusters[i].x,clusters[i].y);

if (trial.done()) {

printf("%s solution in: %i\n",elapsed().c_str(),depth+1);

best_solution.push_back(clusters[i]);

break;

} else {

if (trial.unique() + depth + 1 < max_depth) {

const vector<cluster_result> &solution = dfs_cluster_solve(trial,depth+1,max_depth);

if (solution.size() > 0) {

best_solution = solution;

best_solution.push_back(clusters[i]);

max_depth = depth+best_solution.size();

}

}

}

}

return best_solution;

}

The “standard” method is possibly the fastest way to exclude events in bulk, and works ideally on mostly-empty boards. Non intuitively, clicking the biggest cluster is not the best strategy for a mostly full board. There, a better goal is to click the cluster that forms the biggest groups later. This is a much more complicated thing to calculate, as you have to look ahead one step at every level. The implementation is not terribly difficult, though, as clusters must just be ordered not by the size of the cluster, but by the size of the biggest cluster they create, which is relatively straightforward to figure out with the game abstraction. After some testing of this algorithm, I discovered a better heuristic for finding optimal solutions quickly that is a combination of the this and the “standard” algorithm: order the clusters by the sum of the cluster size and the size of the biggest cluster it creates. You can perhaps convince yourself that this approximates the optimum of removing tiles quickly and creating big groups of tiles. I call this the “lookahead” method.

//returns the moves in backwards order ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

vector<cluster_result> dfs_cluster_lookahead_solve(Board &b, int depth = 0, int max_depth = 48) {

vector<cluster_result> best_solution;

const vector<cluster_result> &clusters = b.cluster();

vector<tuple<cluster_result,Board,int,int>> resorted; //this is way easier in Python

for (int i = 0; i < clusters.size(); i++) {

Board trial(b);

trial.move(clusters[i].x,clusters[i].y);

if (trial.done()) {

printf("%s solution in: %i\n",elapsed().c_str(),depth+1);

best_solution.push_back(clusters[i]);

break;

}

const vector<cluster_result> &next_clusters = trial.cluster();

resorted.push_back(make_tuple(clusters[i],trial,next_clusters[0].num,clusters[i].num));

}

//sort by cluster size + size of biggest created cluster

sort(resorted.begin(),resorted.end(),

[](tuple<cluster_result,Board,int,int> &a, tuple<cluster_result,Board,int,int> &b) {

return get<2>(a)+get<3>(a) > get<2>(b)+get<3>(b);

});

for (int i = 0; i < resorted.size(); i++) {

Board &trial = get<1>(resorted[i]);

if (trial.unique() + depth + 1 < max_depth) {

const vector<cluster_result> &solution = dfs_cluster_lookahead_solve(trial,depth+1,max_depth);

if (solution.size() > 0) {

best_solution = solution;

best_solution.push_back(get<0>(resorted[i]));

max_depth = depth+best_solution.size();

}

}

}

return best_solution;

}

There is almost certainly a better (more complicated) heuristic for ordering clusters. The best heuristic would put the best move first always, while the “lookahead” method cluster ordering only usually puts the best cluster first. This results in the depth first search finding a good solution very quickly, and then spending a long time fruitlessly checking if any better solution exists. The “lookahead” method is also better at more full boards, while “standard” performs very well for more empty boards. Because of this, a hybrid algorithm that tests that uses the “lookahead” method to find a solution quickly for early moves, and then the more lightweight “standard” method to clear other potential solutions for later moves, called “shortlook” (which I leave as an exercise to the reader), ultimately finds solutions faster.

It is probably sufficient for practical purposes to just go with whatever the lookahead algorithm finds within a minute or so. For less practical people, like myself, one might even consider training a neural network to identify the best moves at any stage, and use that as a heuristic… some other time, perhaps.

Profiling

After some fiddling with gcc to prevent it from inlining functions (which does incur a small a performance hit), and building the code with the profiler enabled (-pg arguments),

running a test solve will additionally generate a gmon.out file which contains a binary log of how long each function took and how many times it was executed.

g++ -g -pg -O3 -fno-inline -fno-inline-small-functions crush.cc -o crush

The utility gprof can turn this into a human readable report.

gprof crush gmon.out > report.txt

Then the utilities gprof2dot and dot can turn this report into a graphical representation of the call graph, showing how much time was spent in each function.

gprof2dot -s report.txt | dot -Tsvg -o crush.gprof.svg

As expected, the most time is spent running the contract function as part of a move.

The next biggest slice, perhaps non-intuitively, is the unique function.

Both are called about a 130 million times.

Most of the remaining time is spent in the cluster algorithm, with most of that being spent shuffling memory around when calling standard library routines.

While cluster is much more complicated than unique, it is called far fewer times (7 million), resulting in less overall runtime, and indicating the $N+M<N_{best}$ criteria is sparing some serious computation time.

Example solutions

Here are the solutions to the board shown earlier found by the algorithms described in the previous section. The results include the time taken to find the best solutions along with the time taken to be sure they are the best solutions.

standard

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O Y O

4 | R O R G Y G B Y

3 | R R B G O O R G

2 | B R B O B Y R G

1 | B R Y B B R G G

0 | O Y G G R O R G

GGGGBOYO,RORGYGBY,RRBGOORG,BRBOBYRG,BRYBBRGG,OYGGRORG

Running standard solver...

0:00:00.000 solution in: 19

0:00:00.000 solution in: 18

0:00:00.002 solution in: 17

0:00:00.006 solution in: 16

0:00:00.185 solution in: 15

0:00:01.310 solution in: 14

0:00:06.712 solution in: 13

0:00:14.970 solution in: 12

0:00:56.655 solution in: 11

0:01:35.520 finished

move(7,0) :: G(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O

4 | R O R G Y G Y

3 | R R B G O O B

2 | B R B O B Y R

1 | B R Y B B R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(3,1) :: B(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G O

4 | R O R G G Y

3 | R R B G B O B

2 | B R B G Y Y R

1 | B R Y O O R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(3,1) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G

4 | R O R G O Y

3 | R R B G G O B

2 | B R B G B Y R

1 | B R Y G Y R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(2,0) :: G(9)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | R O Y

3 | R R R O O B

2 | B R B B Y R

1 | B R B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(2,1) :: R(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | Y

3 | O O O B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(3,3) :: O(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(5,0) :: O(1)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y

2 | B B B B R

1 | B B Y Y R O

0 | O Y Y R R R Y

move(4,0) :: R(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 | B B Y

1 | B B B B O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

move(2,1) :: B(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 | Y O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

move(2,0) :: Y(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 | O O

move(3,0) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

lookahead

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O Y O

4 | R O R G Y G B Y

3 | R R B G O O R G

2 | B R B O B Y R G

1 | B R Y B B R G G

0 | O Y G G R O R G

GGGGBOYO,RORGYGBY,RRBGOORG,BRBOBYRG,BRYBBRGG,OYGGRORG

Running lookahead solver...

0:00:00.000 solution in: 16

0:00:00.000 solution in: 15

0:00:00.027 solution in: 14

0:00:00.072 solution in: 13

0:00:22.170 solution in: 12

0:00:35.407 solution in: 11

0:04:41.487 finished

move(7,0) :: G(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O

4 | R O R G Y G Y

3 | R R B G O O B

2 | B R B O B Y R

1 | B R Y B B R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(3,1) :: B(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G O

4 | R O R G G Y

3 | R R B G B O B

2 | B R B G Y Y R

1 | B R Y O O R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(3,1) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G

4 | R O R G O Y

3 | R R B G G O B

2 | B R B G B Y R

1 | B R Y G Y R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

move(2,0) :: G(9)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | R O Y

3 | R R R O O B

2 | B R B B Y R

1 | B R B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(2,1) :: R(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | Y

3 | O O O B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(3,3) :: O(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

move(5,0) :: O(1)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y

2 | B B B B R

1 | B B Y Y R O

0 | O Y Y R R R Y

move(4,0) :: R(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 | B B Y

1 | B B B B O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

move(2,1) :: B(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 | Y O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

move(2,0) :: Y(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 | O O

move(3,0) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

shortlook

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O Y O

4 | R O R G Y G B Y

3 | R R B G O O R G

2 | B R B O B Y R G

1 | B R Y B B R G G

0 | O Y G G R O R G

GGGGBOYO,RORGYGBY,RRBGOORG,BRBOBYRG,BRYBBRGG,OYGGRORG

Running shortlook solver...

0:00:00.000 solution in: 16

0:00:00.000 solution in: 15

0:00:00.001 solution in: 14

0:00:00.008 solution in: 13

0:00:02.466 solution in: 12

0:00:04.009 solution in: 11

0:00:33.595 finished

total clusters: 28

move(7,0) :: G(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G G B O

4 | R O R G Y G Y

3 | R R B G O O B

2 | B R B O B Y R

1 | B R Y B B R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

total clusters: 25

move(3,1) :: B(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G G O

4 | R O R G G Y

3 | R R B G B O B

2 | B R B G Y Y R

1 | B R Y O O R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

total clusters: 22

move(3,1) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 | G G

4 | R O R G O Y

3 | R R B G G O B

2 | B R B G B Y R

1 | B R Y G Y R R O

0 | O Y G G R O R Y

total clusters: 21

move(2,0) :: G(9)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | R O Y

3 | R R R O O B

2 | B R B B Y R

1 | B R B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

total clusters: 16

move(2,1) :: R(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 | Y

3 | O O O B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

total clusters: 13

move(3,3) :: O(3)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y B

2 | B B B Y R

1 | B B Y R R O

0 | O Y Y R O R Y

total clusters: 12

move(5,0) :: O(1)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 | Y

2 | B B B B R

1 | B B Y Y R O

0 | O Y Y R R R Y

total clusters: 8

move(4,0) :: R(5)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 | B B Y

1 | B B B B O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

total clusters: 5

move(2,1) :: B(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 | Y O

0 | O Y Y Y Y Y

total clusters: 3

move(2,0) :: Y(6)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 | O O

total clusters: 1

move(3,0) :: O(2)

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

--+----------------

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |