Detecting neutrinos

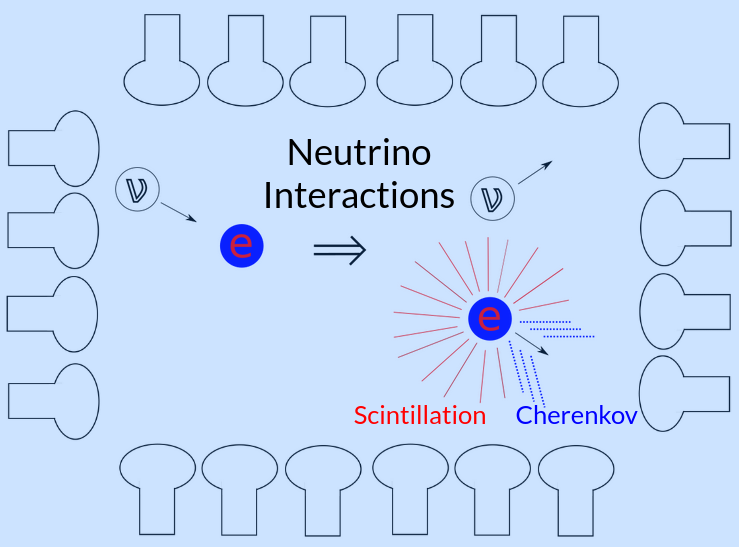

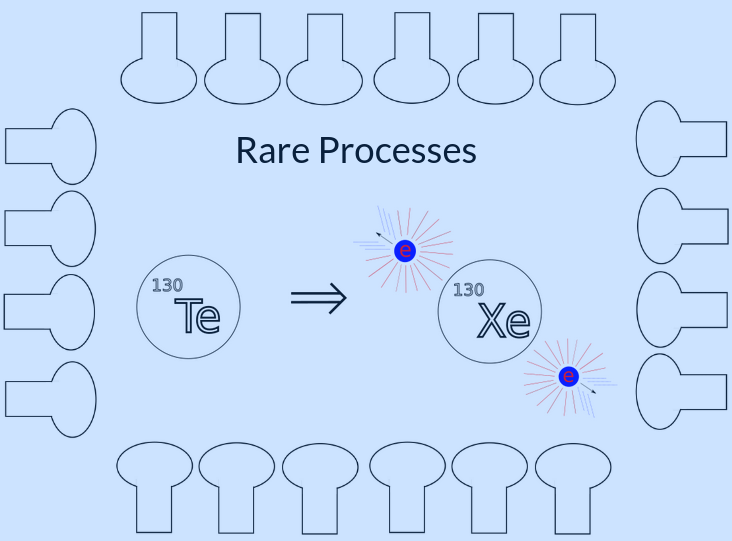

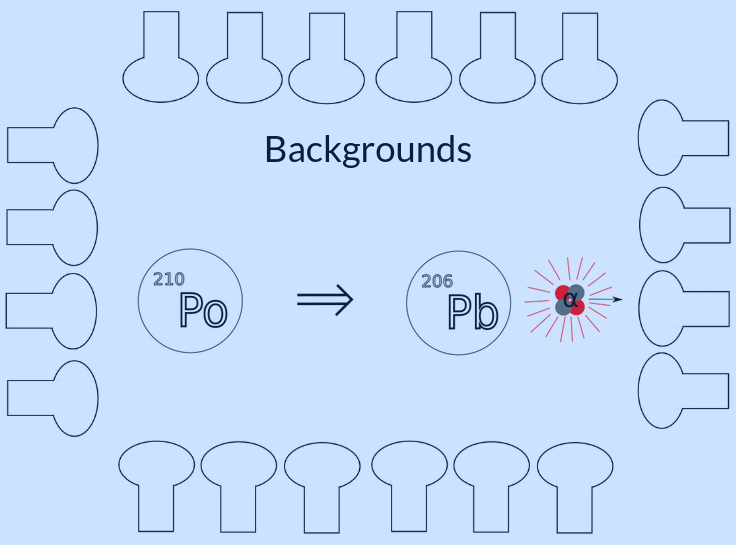

Neutrino interactions produce energetic electrons which in turn produce Cherenkov (directional) and scintillation (isotropic) photons in scintillators. Rare processes like neutrinoless double beta decay, which produces two energetic electrons, can also be studied by neutrino detectors. Any analysis of optical detector data has to deal with radiological materials in the detector, which also produce energetic electrons, and sometimes energetic alpha particles ($^4$He nuclei). The alphas usually have too little energy to produce Cherenkov photons, but still produce scintillation.

Optical neutrino detectors study neutrinos by detecting the photons produced in physical interactions within the detector. These physical interactions could be neutrino signals, which produce high energy electrons. These electrons would produce both directional Cherenkov light, if the energy is above the Cherenkov threshold for the target material, and isotropic scintillation light, if the target material is a scintillator. Due to their exceptional sensitivity to high energy particles, neutrino detectors can also be used to study rare processes, like neutrinoless double beta decay, and must deal with ever-present radioactive background signals in the detector, which all produce light through via the same mechanisms.

The photons detected from this light carry information about the physical interaction, and the following properties are used by most experiments to extract this information:

- The number of photons (intensity of the light) is proportional to the energy lost by the electrons, which is related to the energy of the neutrino.

- The hit time of the photons can be used to reconstruct the position and time of the interaction within the detector.

- The hit topology (of directional Cherenkov photons) carry information on the direction of the electron when it produced the light, since they are produced at a constant angle from the electron direction.

Additional information is carried by these photons, which is not usually measured by experiments:

- The polarization of the photons is random for scintillation, but has a topology for Cherenkov light.

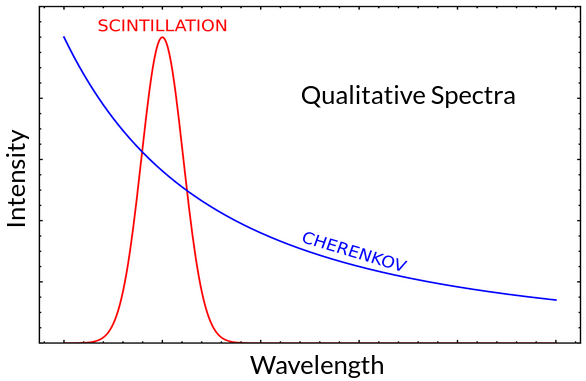

- The wavelength of the photons follow a narrow distribution for scintillation, but have a very broad distribution for Cherenkov.

Cherenkov and scintillation light

The energy, position, and time of the interaction are common inputs to higher-level analyses of detector data. All three of these metrics can be reconstructed from scintillation photons. This is fortunate, because scintillation light can be very bright, and the precision of these metrics is limited by the number of photons detected. The direction is also a useful input to such analyses, though it is only carried by the Cherenkov photons. For scintillator detectors, detecting Cherenkov photons can be very difficult, as there are tens to hundreds of times more detected scintillation than Cherenkov photons. With dim enough scintillation light, or some ability to discriminate Cherenkov from scintillation photons, scintillation detectors can still reconstruct direction.

Some method to discriminate Cherenkov from scintillation photons would do more than allow scintillation detectors to reconstruct direction. Since heavier particles, like the alphas produced in radioactive decays, tend to only produce scintillation light, the lack of Cherenkov photons in those events could be used to identify them. This would significantly improve analyses of scintillator detector data, since these radioactive alpha backgrounds can be similar in energy to more interesting signals and appear at a much higher frequency.

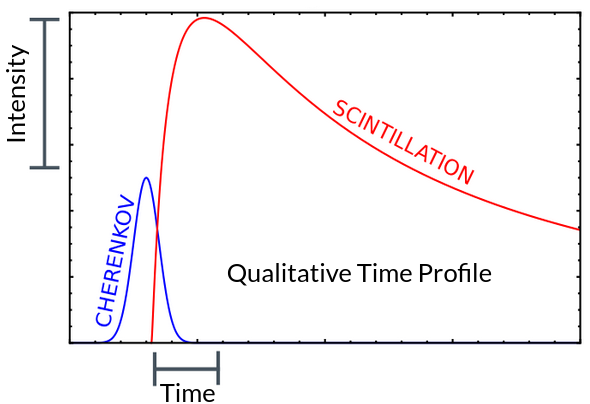

There are two conceptual approaches to distinguishing Cherenkov photons from scintillation photons. The first is to use the detection time, since Cherenkov photons are emitted early in an interaction, whereas scintillation photons have a long time distribution.

By selecting an early population of photons, a pure selection of Cherenkov photons can be obtained1.

The second approach, referred to as “spectral photon sorting,” leverages the fact that Cherenkov and scintillation photons have distinct wavelength distributions.

By diverting long and short wavelength photons to different light detectors, a population of pure Cherenkov (long wavelength) photons can be identified2.

Spectral photon sorting with dichroic filters

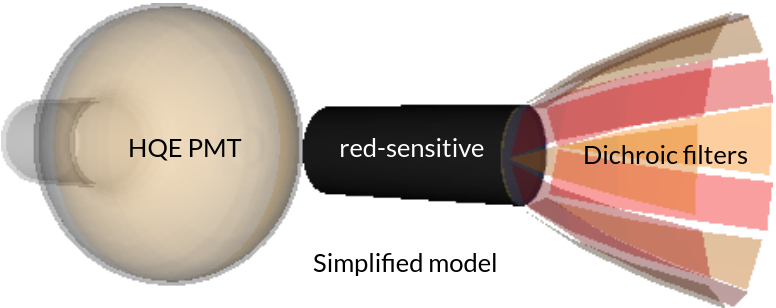

Dichroic filters are thin-film reflectors that reflect photons above (or below) a certain wavelength, while transmitting other wavelengths. If a light concentrator like a Winston cone is constructed out of short-pass dichroic filters, long wavelengths will be concentrated while short wavelengths are transmitted. A device consisting of such a dichroic Winston cone is known as a dichroicon3 and a simulated dichroicon is depicted below.

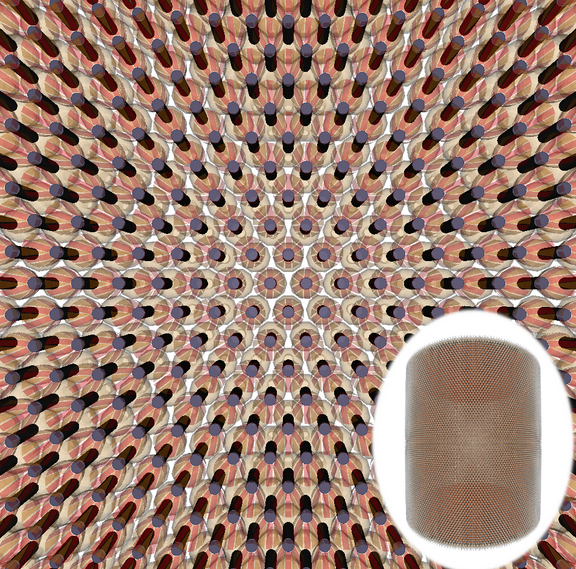

Using this model in Chroma, a very large neutrino detector with 50 kilotons of liquid scintillator as a target material can be simulated, which uses dichroicons as the light detecting elements.

A right cylinder detector with 50 kt of liquid scintillator using dichroicon light detectors on the cylindrical boundary. The background is the detail of one wall of the detector, showing tiled dichroicons, while the full detector is shown in an oval inset.

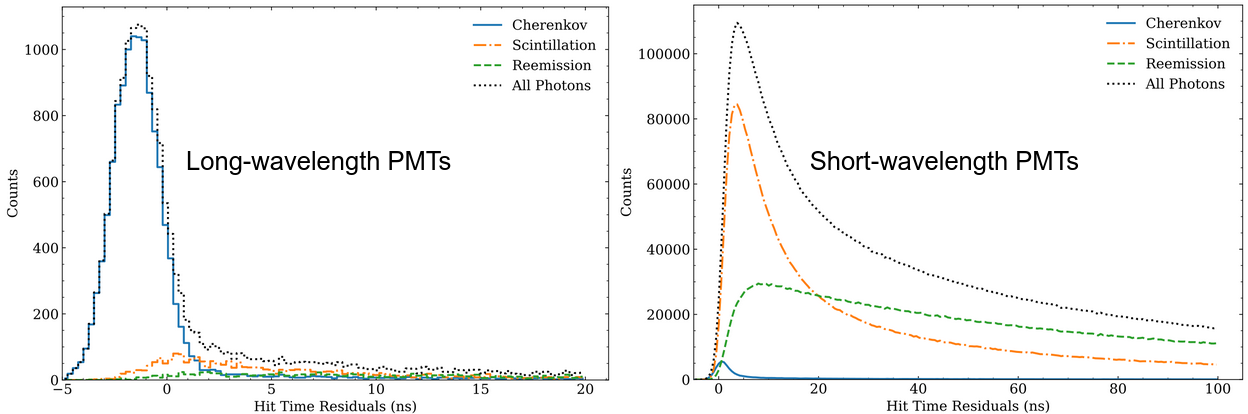

This simulation model allows the spectral photon sorting capabilities of the dichroicon to be tested in a realistic way, as all critical parts from the fundamental physics to the optics are accurately simulated. As a benchmark, electrons with 5 MeV of energy can be simulated in the center of this detector, and the time distribution of the detected photons can be plotted. Because this is a simulation, the true nature of each photon is known, and it an be conclusively shown that prompt Cherenkov photons are seen on the long wavelength PMTs, while the short wavelength PMTs are dominated by scintillation photons.

The time distributions for photons detected on long and short wavelength PMTs from a liquid scintillator neutrino detector using dichroicons when 5 MeV electrons are simulated in the center.

Reducing backgrounds with spectral photon sorting

To demonstrate the background reduction capabilities resulting from identification of Cherenkov photons, three different types of events with the same “visible energy” (mean number of detected photons) were simulated in the detector:

- Single $\beta$ decays, which are just high energy electrons resulting from radioactive decay.

- Single $\alpha$ decays, which are just high energy Helium nuclei resulting from radioactive decay.

- Neutrinoless double beta decay ($0\nu\beta\beta$) events from $^{130}$Te, which are two back-to-back electrons resulting from a hypothetical double beta decay where no neutrinos are emitted.

For a neutrinoless double beta decay analysis, event class 3 would be the primary signal, while event classes 1 and 2 would be (common) backgrounds: events occurring at the same energy as the signal. A high level analysis would have to reject these backgrounds in some way. There are many ways to accomplish this, and the most straightforward is to use knowledge of the energy spectra of event classes 1 and 2 to constrain the number of events of those classes at the discrete energy of the class 3 events by measuring their rates at other energies. However, if the number of events in class 1 and 2 are very large compared to class 3, which can happen because class 3 is very very rare (if it occurs at all), the sensitivity to class 3 can be significantly reduced. Basically, if the measurement of class 1 and 2 suggests there will be 1000 background events around the energy of class 3, observing 1001 events is not very significant. However, if the expectation from the analysis is that there is only 1 background event in that energy rate, observing 2 events is much more significant, even though both scenarios are an excess of 1 event.

To mitigate this sensitivity reduction, robust algorithms to tag or reject background events, like classes 1 and 2, can be used to remove such events from an analysis, or provide a better statistical handle for estimating the number of events. The class 2 ($\alpha$) events would be below Cherenkov threshold, and therefore not produce Cherenkov light. This implies there would be notably fewer long wavelength photons in a sample of class 2. Class 1 and 3 are much more similar, both being electrons, however a single electron with the same visible energy as two electrons combined will tend to produce more Cherenkov light. This is ultimately because the single electron spends more time at energies above the Cherenkov threshold than when the same energy is divided between two electrons.

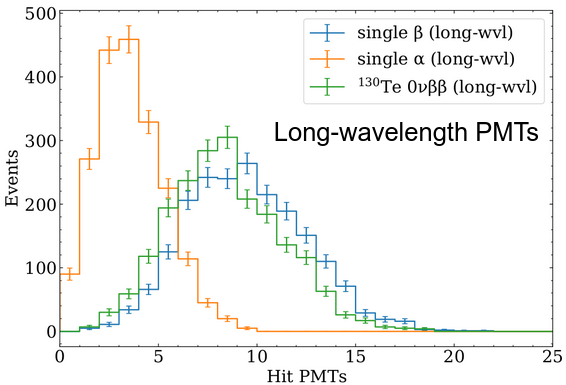

After analyzing simulations of these three conditions in the detector model, a histogram of the number of long wavelength PMTs that detected any photons can be made for each class of event:

The distribution of long wavelength PMTs that detected any photons (hit PMTs) for the three event classes.

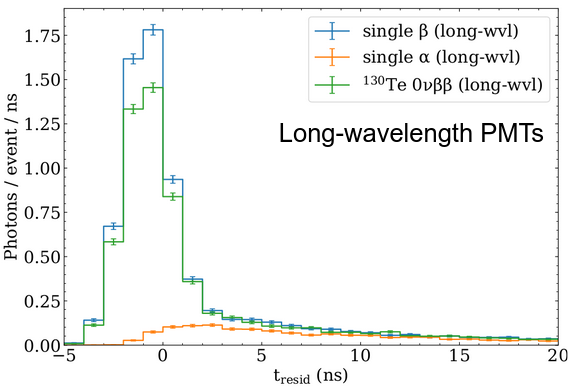

This figure shows that the spectral sorting detector model can distinguish between different types of particle interactions based on the very simple metric of number of hit PMTs, as the shapes of the distributions are different in a statistically significant way for each class. There is some scintillation light detected by the long wavelength PMTs, due to the imperfect nature of dichroic filters modeled in this simulation. That this is scintillation light can be easily seen in the time distribution of the detected photons, where Cherenkov photons are prompt, and scintillation photons have a much broader time distribution:

The time residual distribution of long wavelength PMTs that detected any photons (hit PMTs) for the three event classes. Note the very different shapes of $\alpha$ events (no Cherenkov) and $\beta$ events (with Cherenkov).

With different filters, or a modified geometry, this scintillation light could reduced to significantly improve the ability to tag class 2 ($\alpha$) events. The ability to discriminate single $\beta$ from double $\beta$ events is not as strong, however this metric does not make use of Cherenkov topology at all. Single $\beta$ would produce light in only one direction (one “ring”) while double $\beta$ would produce light in two directions (two “rings”). This is something that would be incredibly hard to detect with a traditional scintillation detector, but is possible with spectral photon sorting and dichroicons.

-

MeV-scale performance of water-based and pure liquid scintillator detectors. Phys. Rev. D 103, 052004 (2021). ↩︎

-

Cherenkov and scintillation light separation using wavelength in LAB based liquid scintillator JINST 14 T05001 (2019) ↩︎

-

The Dichroicon: Spectral Photon Sorting For Large-Scale Cherenkov and Scintillation Detectors. Phys. Rev. D 101, 072002 (2020) ↩︎