The last astrophotography post covered all the details on the technique for capturing deep-sky images and went into some detail about precisely how to interpret these images. Check it out if you’re not sure what you’re seeing below. The only downside of the last post is that it only showcased the “best” images of various different types. Unfortunately, the “best” criteria ruled out a lot of what I consider to be more interesting images: other galaxies. I did get the Whirlpool and Triangulum galaxies in, but these are among the brightest. The Leo Triplet image is more typical of the majority of galaxies to image: small enough to be near typical resolution limits, pretty dim, and perhaps a bit hard to appreciate if you don’t know what you’re looking at.

I’ll try to help with the latter part by starting “nearby” at a meager 2.5 million light years and end up over 300 million light years away.

An aside on imaging distant galaxies

M66 from the Leo Triplet is a pretty typical medium-sized, medium-brightness (apparent) galaxy, which makes this a pretty good image (if I do say so myself; compare to what is pictured on Wikipedia) given the constraints dealt with. M66 is around 9’ by 4’ (arcminutes) which comes out 540px by 240px (pixels) with my setup. More pixels would not help much, as I’m around 1" (arcsecond) – the seeing resolution limit – per pixel.

Due largely to availability at the time, most of my images were taken with an unmodified Sony α7C camera, which is tailored to capturing broadband starlight in the visible spectrum (from the Sun, usually, but applies to other stars as well). The built-in filtering of light to achieve this makes most standard cameras less than ideal for capturing images of emission nebula, as a lot of the narrowband emission light gets blocked, even if narrowband filters are used to select only the desired wavelengths. Even with this penalty, five of eight of the “best” images ended up being emission nebula simply because galaxies are very far away and therefore typically small and dim as they appear to us in the sky — i.e. they have low apparent brightness and small apparent size, while being in fact quite large and bright.

The low apparent brightness of galaxies makes it quite difficult to extract a low-noise image from light polluted areas that still captures the fainter details. Unlike emission nebula, narrowband filtering cannot be employed to select out only the desired features, as the brightness of a galaxy is broadband starlight. The small apparent size means that atmospheric disturbances are a limiting factor to how much detail can be resolved, even with superb optics and high resolution camera sensors. These factors puts imaging galaxies with a standard camera on more even footing with dedicated OSC or monochrome astrophotography cameras, while still being a nice challenge. Excellent calibration, minimal light leaks, and long total exposure times are needed to achieve the results below.

M31 – Andromeda Galaxy (2.5 Mly)

M31 and friends from September 14, 2024 – $29 \times 3 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (1h27m total) with the ASI2600MC-Pro @ -10C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. Note the lower black level achieved with the ASI2600MC-Pro images.

M31 from November 2, 2023 – $120 \times 30 \mathrm{sec}$ exposures (1h total) with my Sony α7C using a 300mm lens at F/9 on a Star Adventurer 2i mount. Processed with Siril.

Spiral galaxies, like ours and Andromeda, have discrete visible structures such as a bright bulbous core region surrounded by a flatter dimmer disk region that contain one or many spiral regions of higher star density, and a very faint diffuse halo of stars in orbits outside the primary disk. Almost all of the brightness is due to starlight, with some large star forming nebula visible as well. Dark features are cold clouds of gas or dust that block light from stars further in the background. Like other galaxies, the detail of the spirals and exterior disk regions are quite faint and present a challenge

M31 and friends from September 14, 2024 – $30 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (2h total) with the Sony α7C. Acquired with NINA and PHD2. Processed with Siril. Note the perspective flip, which the Sony body performs but the ZWO camera does not.

M33 – Triangulum Galaxy (3.2 Mly)

M31 from September 7, 2024 – $40 \times 5 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3h20m total) with the ASI2600MC-Pro @ -10C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. Note the lower black levels achieved with the ASI2600MC-Pro images.

M31 from September 7, 2024 – $40 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3h30m total) with my Sony α7C using a 300mm lens at F/7.1 on a Star Adventurer 2i mount. Processed with Siril.

Similar to Andromeda, the image above is from my dedicated astro camera, with the right and below images being from a lens and telescope respectively, paired with my full frame body. Again, far more detail and halo can be seen with the image using the dedicated astro camera, though some amount of this is down to me learning to take better images. Completely by accident, these all have similar exposure times, so an interesting comparison set. The “complete accident” may just be the longest time Triangulum is visible from my front yard, as these were all shot in single nights.

M31 from September 7, 2024 – $52 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3h28m total) with the Sony α7C. Acquired with NINA and PHD2. Processed with Siril. Note the perspective flip, which the Sony body performs but the ZWO camera does not.

M81 & M82 – Bode’s Galaxy & Cigar Galaxy (12 Mly)

M81 and M82 from February 7, 2024 – $9 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (36m total) with the Sony α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. This was taken at the end of a session, resulting in low integration time and therefore high noise.

Going further out in distance, Bode’s galaxy (on the left) resides nearly 12 million light years away and is a decent 96 thousand light years across, appearing 27’ by 14’, which is a bit smaller than a half moon. Bode’s galaxy is pretty standard and has two long spiral arms with a decent amount of dust structure for detail. This picture does not do it justice, at only half an hour exposure, but I’m planning a revisit soon. Everything else from here on is too faint to get away with such a short exposure time, and you would be hard-pressed to see anything remotely like these images in a consumer-grade telescope visually.

More interesting is the smaller Cigar galaxy off to the right, which is at about the same distance as, and clustered with, Bode’s galaxy. The Cigar galaxy is nominally spiral as well, but is edge-on, showing the disk as a line. Some dust clouds can be seen on the bright glow of the disk. The Cigar galaxy is actively undergoing massive star formation, making it a starburst galaxy, possibly triggered by the proximity of Bode’s galaxy, and is emitting huge amounts of hot gas from the core. I’ll need to spend more time on this target to see the fainter details.

NGC 2403 (10 Mly)

M51 from February 8, 2024 – $85\times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (5h45m total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril.

Not far from M81, and in fact in the same cluster, is a spiral galaxy by no other name than NGC 2403 (and several other catalog numbers) at 10 million light years. The lack of a name is a bit surprising to me, as it is not too small in apparent size, 22’ by 12’, and not much dimmer than Bode’s galaxy in apparent brightness. NGC 2403 tends to remind people of Triangulum, having a textbook multi-arm spiral. In actually size it is just a bit smaller at 50 thousand light years across.

NGC 253 – Sculptor Galaxy (11 Mly)

NGC 253 from October 5, 2024 – $20 \times 5 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (4h20m total) with the ASI2600MC-Pro @ -10C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. Note that this was taken with a cooled camera and has substantially less noise.

Sometimes called the Silver Dollar galaxy, the Sculptor galaxy is a starburst galaxy like the Cigar galaxy. It’s around 11 million light years away, and has an apparent size of 27’ by 7’, as its nearly edge on. A lot of detail can be seen in the dust in the disk, and this is one of the few smaller galaxies imaged with my higher resolution dedicated astro camera.

M51 – Whirlpool Galaxy (23 Mly)

M51 from March 21, 2024 – $45 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (3hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with oscdeeppy. This is one of my favorites, even if the flat calibrations were a bit off — note a darker region to the lower left of the galaxy due to miscalibration.

The Whirlpool Galaxy got its spotlight in volume one of this series, but this is image is very cool because there’s great detail on the spiral arms due largely to the three hours total integration, and the subject itself is a pair of interacting — i.e. currently colliding — galaxies. Keeping the apparent size trend alive, this galaxy at 23 million light years away and an average 77 thousand light years across is only 11’ by 7’ in the sky.

M101 – Pinwheel Galaxy (21 Mly)

M51 from Feburary 24, 2024 – $120 \times 2 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (6hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. The flat calibrations were a bit off here as well — a darker region to the upper right of the galaxy.

Yet another spiral galaxy (and not the last), the Pinwheel galaxy is notable for its many long spiral arms and being face-on to appear as its namesake. The Pinwheel galaxy is about the same distance as the Whirlpool galaxy, at 21 million light years, but in a different direction. Despite its distance, it is relatively large in apparent size at 28’ across, making it even bigger in actual size than Andromeda at 170 thousand light years across.

M106 (23 Mly)

M106 from Mar 22, 2024 – $45 \times 2 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (1h30m total) with the Sony α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril. I took this before the M51 image, waiting for M51 to become visible, just to practice. It only has dark and bias calibration, unfortunately.

M106 has a few nice background galaxies in frame, including one with an edge-on band of dust, making a for a nice image. This galaxy is around 23 million light years away (in yet another direciton), and has an apparent size of 19’ x 7’, revealing it is also on the large side at 135 thousand light years across. Bigger than the Milky Way but smaller than Andromeda. The bright central disk and much fainter extended halo make this a challenging target in high light pollution, but there’s a great deal visible in this image already.

Leo Triplet (35 Mly)

M65 M64 NGC 3628 from March 29, 2024 – $60 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (4hr total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril.

I covered this one in the previous post, but I’ll use it to introduce galactic clusters as interesting targets for imaging as galaxies start getting smaller and fainter. Here the three galaxies are all near each other and form their own galactic group around 35 million light years away. They are all Milky-Way-sized at around 90 thousand light years across, covering 9’ apparent size in the sky, with the long axis of NGC 3628 being 14’. With clusters, a variety of different galactic forms can be visible, and more than one object being present makes for more interesting framing. Here it is very fortunate to see three distinct, resolvable, spiral galaxies so close together, even if one is edge on.

M100 – Mirror Galaxy (55 Mly)

M100 from April 14, 2024 – $65 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (4h20m total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril.

A tight crop of M100, revealing the limiting resolution. Three smaller elliptical galaxies also in the Virgo cluster are seen as the three fuzzy dots in the image.

All the images so far have been cropped to very similar fields of view, so that the relative sizes of the galaxies are true, but I include a crop to the left so that the detail, or lack thereof, is easier to make out without inspecting the full resolution image.

The Virgo cluster is a structure of many thousands galaxies similar to the Local Group that contains our galaxy, Andromeda, the Milky Way, etc, and to the M81 group, the M51 group, the M101 group, and the M106 group, and the Leo Triplet that came before, except much larger. Ultimately the Virgo cluster is the center of the Virgo supercluster, a structure of galaxy clusters spanning 110 million light years containing the Local Group and all other nearby galactic clusters. Because the Virgo cluster is so far away, its numerous galaxies appear in a relatively compact part of the sky, allowing many to be in the same frame at the same time.

Markarian’s Chain (55 Mly)

M84, M86, NGC 4435, NGC 4435, NGC 4461, NGC 4472, NGC 4477, NGC 4457, and friends from June 2, 2024 – $50 \times 5 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (4h10m total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril especially for this post.

Also in the Virgo cluster, so around 55 million light years away, is a collection of many elliptical and irregular galaxies forming an apparent arc in the sky known as Markarian’s Chain. Elliptical galaxies are not quite as exciting as spiral galaxies, as they are mostly halos, but will sometimes contain dust clouds. The largest of these constituent galaxies is around 6’ across, making it around Milky-Way-size, 90 thousand light years across. While the arc arrangement is a purely apparent phenomenon (meaning it depends on our perspective) these galaxies are all in the Virgo cluster and so are interacting with each other with gravity.

Stephen’s Quintet & Deer Lick Group (40-350 Mly)

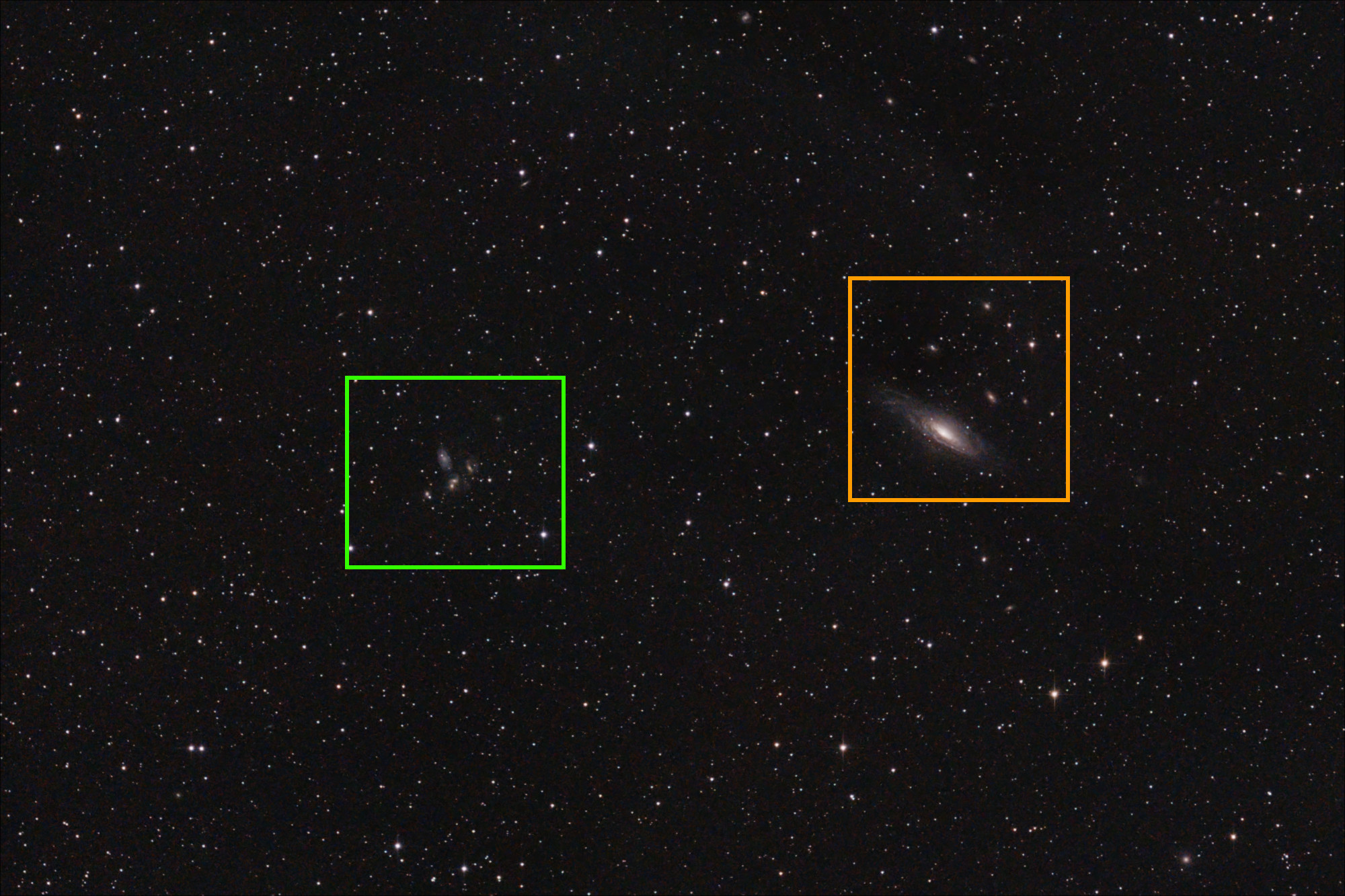

NGC 7331 (the largest galaxy) and friends from August 22, 2024 – $11 \times 4 \mathrm{min}$ exposures (44m total) with the α7C. Acquired with INDI + KStars/Ekos. Processed with Siril especially for this post. This was a brutally short exposure, but the target went behind a tree. Noise reduction carried the day here.

To aid it identifying the small galaxies, the Deer Lick Group is marked in orange, with Stephen’s Quintet marked in green.

Also in frame, to the left of center, is a visual group of five similar apparent-sized galaxies around 2’ across known as Stephen’s Quintet. One of these galaxies, NGC 7320, is in fact quite small, relatively nearby at 40 million light years, and may form a true group with NGC 7331 as its satellite. The remaining four are physically much larger, known as HCG 92, and form a true group again in the neighborhood of 300 million light years away.

The galaxies at the hundreds of millions of light year ranges are the furthest I’ll likely be able to resolve any detail on, but there are objects at billions of light years that are bright enough to at least be seen. More on that later.

>> Home